2025.11.13 THROW BACK THURSDAY - WALT COLEMAN III PLUS CLASS NEWS

THROW BACK THURSDAY - WALT COLEMAN III PLUS CLASS NEWS

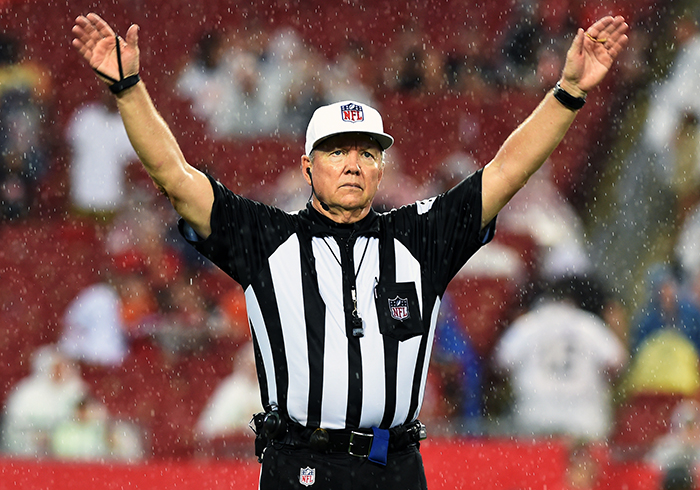

Walt Coleman III has held two jobs in his life — in dairy and as a referee — and in both he carried on the family business. Coleman’s tenure with Coleman Dairy, now Hiland Dairy, started when he was 12 and has continued to this day through changing times, changing tastes and changing ownership, if not handlers. His time in stripes stretches back almost as far, with nearly five decades in the high school, college and pro ranks until his retirement after the 2018 season. “I got into the dairy business because it was a family deal. I got into officiating because of the same thing,” he said. “My uncle was a high school and college officiate. My dad was a high school and college officiate; he was in the Southwest Conference for 26 seasons. I was around officiating just like I was around the dairy business my whole life.” Coleman served both professions with such distinction it is hard to say which of his jobs he is best identified with. In Arkansas, Coleman and his family have been known in the business community for five generations, during which time they provided jobs for thousands of employees. As a referee — try though he might to live by the mantra that the best-called game is one where officials are invisible — he became well-recognized in one of the biggest and most successful sports leagues in the world. You would never know any of this by his modest — that is, cramped — office at the top of a back flight of stairs at the Hiland plant or the surprisingly few football mementos he keeps on display there. Here, he is not Mr. Coleman or Referee No. 65. Around here, he is just Walt, a son of the Natural State, just like anyone else. “I have been very fortunate in my life to be around people who were really talented and taught me,” he said. “It helped me so much because I knew what to expect. I knew how I was supposed to act and how I was supposed to react. I didn’t have to learn by trial and error.

“I was also very fortunate to be in a great family, starting with my wife, Cynthia, who hung in there and raised two kids. I spent a lot of time dealing with the NFL, and if it wasn’t for my brothers and my dad, who helped run the business, and all the other people involved here that did everything, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. You have to have a support group, and I was very fortunate to have that.” Walt Coleman was born the eldest of four boys. He grew up in a house on Asher Avenue in Little Rock handed down by his grandparents that backed up to the 200-acre Coleman Dairy spread founded in 1862 by Eleithet B. Coleman. As a youth, he did odd jobs around the facility and, like most children in family businesses, continued to work throughout his high school years. “Growing up, I had a job every summer working in the plant and running home delivery routes, which was very difficult,” he said. “My route started at 3 a.m., and I had to be up working while all my buddies were out doing all kinds of fun things.” Despite his schedule, Coleman excelled in football and basketball at Little Rock Central High School and was such a standout in baseball that he would go on to play shortstop for the Razorbacks under brand-new skipper, Norm DeBriyn. A self-described “good-field, no-hit guy,” Coleman earned three varsity letters between 1972 and 1974. After graduation, Coleman returned to Little Rock with a business degree and the dream of one day succeeding his father, Walter Carpenter “Buddy” Coleman, as CEO. Today, he points with pride to the many innovations the company introduced both preceding and during his tenure, including installing pasteurization equipment in the 1930s and investing heavily in marketing and advertising gimmicks to drum up the Coleman brand. “We were one of the first dairies in this part of the country that put in blow molding equipment to create plastic milk jugs,” he said. “We were also the first dairy in the country to use handheld devices on our route trucks. That was something that I did. Everything was manual then. We had to write the tickets out. I put handheld computers in back in the late ‘70s, which everybody uses now. “We had many, many competitors, plus we had vertically integrated customers like Kroger who had their own dairy plants. When your customers are also in your business, it makes things very difficult. Some of the things we did as far as upgrading equipment and technology and so forth gave us the ability to survive when other people didn’t.” In 1995, Coleman Dairy sold and, after its parent company changed hands several times over the next decade, became part of an Illinois-based company, which positioned the Little Rock operation as a division of Hiland Dairy. As a nod of respect, the new owners held off changing the name until Coleman Dairy reached its 150th year in business.

“We didn’t want to sell, but if we didn’t, were we going to be able to survive? Would we get in a situation where we might have to file bankruptcy? Could all our employees lose their jobs?” Coleman said. “That was an unbelievably hard decision, but when we put all the facts together and we looked at the 250 people, second- and third-generation people, who were working for us, the decision we made turned out to be tremendous.” Coleman’s time officiating began shortly after he graduated from college as just another fresh-faced 22-year-old looking to pay his dues and work his way up the ranks. Being the son and nephew of officials helped the younger Coleman land games and also instilled a code of decorum into what he was doing. “The older guys taught me that as an official, you’re doing something that’s very necessary, that nobody appreciated and that was going to be difficult,” he said. “Also, that you were the integrity of the game, and how you handled yourself and the perception you gave people was really important. They showed me how to carry myself when things were not going very well. “My dad would say, ‘Walt, if a coach starts giving you a hard time, step out on the field. Don’t stand right there in his throat. Step out four or five yards so you’ve got a separation. Then, when it’s about time for play to start, you can back up to the sideline. Be professional, understand they have a tough job, and walk in their shoes.’ I always tried to do that.” Coleman’s dream was to officiate big-time college football like his father. He made it but reached a crossroads whereby he had to gauge the risk-reward of working a Razorback game and the impact it might have on the company. “If I was to make a mistake or even get it right but [sportswriter] Orville Henry decided it was wrong and blasted it in the paper, we could lose half our customers,” he said. “I had to do something different if I wanted to stay in the dairy business.” The quandary led Coleman to reluctantly apply to the NFL, doubting the whole time much would come of it. To his surprise, a call came requesting an interview, and before he knew it, he was in Chicago’s Soldier Field for a 1989 tilt between the Cincinnati Bengals and the hometown Bears. His first six years in the league was as line judge, which put him directly in coaches’ line of fire. “[Buffalo Bills’] Marv Levy had a Ph.D. in English, but he didn’t use anything but four-letter words when I was on the sideline with him,” he said. “[Las Vegas Raiders’] Jon Gruden was terrible; his favorite word starts with ‘F.’ Heck, I stood in front of [Dallas Cowboys’] Jimmy Johnson and [Miami Dolphins’] Don Shula and [Pittsburgh Steelers’] Bill Cowher back when I was a line judge, and they could sure visit with me. It wasn’t always pretty.” Nearly three decades as an NFL referee invested Coleman with a multitude of stories and put him in the middle of some of the most memorable games in league history, as well as many that were merely on the schedule. For each one, Coleman brought his very best, despite the conditions or circumstances.

“There was a playoff game in Minnesota where it was so cold, it was minus-25 at kickoff. It was just brutal as far as how cold it was,” he said. “In Cleveland, they threw stuff out of the Dog Pound onto the field all the time before the NFL got smart and put cameras in the stadiums. “I worked the Bounty Bowl between Dallas and Philadelphia where it had snowed, and back then, they didn’t make them clear out the stadium. Eagles fans were throwing snowballs and everything else at Jimmy Johnson and all the Cowboys players. Philadelphia fans were tough, man, they booed their own quarterback, they booed Santa Claus! Fans — that’s short for fanatic.” All of it takes a back seat to Jan. 19, 2002, and the 2001 AFC Divisional Playoff game contested in a snowstorm between the then-Oakland Raiders and New England Patriots, a game which would cement Coleman’s legacy for all time. Down late, second-year Patriots quarterback Tom Brady, the relatively unknown 199th pick of the previous year’s draft, appeared to fumble the ball after a hit by Oakland’s Charles Woodson. Using the early iteration of instant replay review, Coleman determined Brady’s arm was coming forward and overturned the fumble as an incomplete pass, which kept the ball in New England’s possession. The Patriots would win the game in overtime. NFL Network ranked the call the second-most impactful in league history, and entire documentaries have since been made about the so-called Tuck Rule Game. After that, New England advanced to and won its first championship, launching a dynasty that would include playing in eight more Super Bowls in 17 years. Brady, widely regarded as the greatest quarterback of all time, would later credit Coleman’s call with springboarding his legendary career, which would eventually include seven Super Bowl rings. Raider Nation, led by soon-to-be-disgraced ex-coach Jon Gruden, would never forgive Coleman. “That was my call. It was all me, and back then, I had 60 seconds. When that 60 seconds was up, that [replay] screen would go black, and if you hadn’t decided, you were up a damn creek,” Coleman said. “It was just huge. They’re still talking about it.” When all was said and done, Coleman would work two conference championship games and serve as alternate referee for three Super Bowls. He also inspired his son, Walt Coleman IV, to officiate all the way to the pros, starting in 2015. Four seasons later, he retired as the longest-tenured current official, and following his last regular season game, which involved New England, the Patriots awarded him the game ball. Only one NFL referee resides in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and while being the second would be nice, Coleman, who is enshrined in the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame with his dad, is content. “I was doing a podcast with a guy who wanted to talk to me from a mental standpoint about all the abuse and stuff I had taken. He wanted to know how that affected me,” Coleman said. “I told him when 80,000 people would be booing me, I thought it was great because I knew I was doing something. I was involved. “In fact, I do some motivational speaking now, and the first thing I do is I ask everybody in the audience to boo. It’s just part of it. I sure hate making a mistake, but the booing and all that stuff didn’t bother me because that’s what’s supposed to happen.”

Arkansas Money and Politics by Dwain Hebda

1956 CLASS NEWS

We lost a wonderful Classmate this past Sunday. Jackie had been living in Presbyterian Village for a couple of years now with a wonderful family who visited often.

Jack Bush of Sheridan, Arkansas | 1938 - 2025 | Obituary

Robert Earle Bush, Jr., known to many as just “Jack”, was born September 14, 1938 in Little Rock, Arkansas, the son of the late Robert E. Bush, Sr. and Rose Bernier Bush. He was a member of the First United Methodist Church of Sheridan and proudly served in the United States Navy. Haskell Dickinson of McGeorge Construction expressed gratitude for Jack’s 40+ years of dedicated service. He recalled A+ effort every day, a splendid safety record despite the hazards of mining, managing a very diversified crew, and being a great developer of people. He also noted Jack’s exceptional knowledge of their equipment capability greatly adding value in bidding and managing projects. Jack thoroughly enjoyed the outdoors, whether coon hunting with his dogs or working his horses with the kids. The family shared fond memories of their PawPaw and he treated his non-biological children the same as his biological children. Eating grandmother Rose’s peanut butter cookies with his baby brother put a smile on his face, and everyone remembered receiving cards with his sweet signature every birthday and Christmas. Jack didn’t just congratulate his family for milestone events, he showed up to celebrate with you. Jack loved in his own unique and unmistakable way. He allowed his children to fail in order to grow, but faithfully provided a safety net. He was patient, steady, and consistent and you always knew what you were going to get, even if you weren’t going to like it! Mr. Bush died Sunday, November 9, 2025 at Presbyterian Village in Little Rock, at the age of 87. In addition to his parents, he was preceded in death by his wives, Virginia Bush, who was the mother of his children, and Wanda Bush; son, Robert “Bobby” Earle Bush, III; sister, Susie Braucksieker. Survivors include his daughters, Susan Brown (Nick) of Little Rock, Mary Catherine Harcourt (Hollie) of Fayetteville; step-daughter, Sonja White (Mitch) of Cowetta, Oklahoma; brother, Bill Bush (Retha) of Little Rock; grandchildren, Bonnie (Samir) Boudieb, Chesley (Allison) Skipper, Nolan (Lori) Brown, Jaime (RJ) Skipper, Lana Brown, Amanda (Terry) Donaho, JC (Ilana) Harcourt, Chad (Tara) Harcourt, Braiden White, Karsyn White; 10 great grandchildren. He is also survived by numerous other extended family members and many friends.

Visitation is 10 a.m. Friday, November 14, 2025 with memorial service to follow at 11 a.m. at Memorial Gardens Funeral Home Chapel in Sheridan. Chad Harcourt, Jack’s grandson is officiating. Burial will be at Bethel Cemetery at the Ico Community.

Serving as Pallbearers: Hollie Henderson, Nick Brown, Gary Brewer, Paul Brewer, JC Harcourt, Nolan Brown, Ches Skipper, RJ Webber and Honorary Pallbearer, Braiden White.

Memorials may be made to the Presbyterian Village Foundation, 510 North Brookside Drive, Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 or to the charity or organization of your choice.

GIRLS' CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON will be held on MONDAY, DECEMBER 8, 11:30AM. Mark your calendar now

Let her know as soon as you know that you will be able to attend so she will be able to feed all of us!!!!!!

Now here's two guys livin' it up! Joel Hicks and his son, Don, are in Portland, OR, to hear Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass!!!!

1955 CLASS NEWS

KAY "KK" SMITH PATTON, age 88, died Sunday, November 2, 2025, in Leawood, Kan. She was born October 11, 1937, in Corsicana, Texas, to the late William J. and Irma H. Smith. She was preceded in death by her husband of 60 years, William L. Patton, Jr. She is survived by three daughters: Holly P. Beineman (Don), Ann D. Patton (Jack), and Katherine D. Patton (Alaric); and granddaughters, Alexandra Beineman (Brynna), and Carson Beineman. Kay moved to Little Rock in 1940, where she was educated in Little Rock public schools. Upon graduating Little Rock Central High School in 1954, she attended Randolph-Macon Women's College. Upon graduating college in 1959, Kay became part of the first group of 40 students allowed to study behind the Iron Curtain in the Soviet Union, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. She met Bill Patton in 1960, and they married in January of 1961. She taught Western Civilization at the University of Arkansas while she earned an MA in history and Bill earned a law degree. They returned to Little Rock, and started their family, to whom she was devoted. Kay dedicated her professional life to social services and children, especially those who needed a voice. Her accomplishments were too many to count, and the impact she had on the city of Little Rock and beyond will be remembered forever. She never stopped seeing the magic in people and in life, and her glass overflowed with optimism, compassion, and humor. She never stopped learning, she never stopped teaching, and she was always interested in other people's story. She considered her life vast and interesting. Her infectious smile and laughter reminded us all that joy could be found in even the simplest moments. We will remember her not only for what she gave to us as her daughters, and to all whose lives she touched, but for how she lived: with courage, grace, and an unshakable faith in love. The family will be forever grateful to the caregivers who, with loving hearts and kind hands, were with her this past year. In lieu of flowers, donations in her honor may be made to The Farmers House in Kansas City, Mo.

************************************************************************************************

Joe Crow recently found this 1969 photo on his phone. Double click to enlarge.

Sad News: Everyone on the front row is gone. Happier News: Other than Tony Owens and Gwen Shepherd's sister, Janice (I think that's Janice),

we're hoping to see all the others at our 70th Reunion next April 25, 2026!!!!

Front row: Doris Kerr, Mary Catherine Kline, Dian Warner, Mollie Beth Dicus

Second row: Clarience Smith, Janice Shepherd, Nancy Newsom, Sandy Snow

Back row: Peter Hartstein, Gwen Shepherd, Judy Callaway, Tony Owens and Syd Orton

******************************************************************************************************

OK, you know this had to come from Joe Crow . . . but it is pretty funny . . . even while you're groaning:

ML